In September 2015, just a few months before the world signed up to the Paris Agreement on climate change, a number of huge forest fires erupted across Indonesian Sumatra and Borneo, darkening the skies across Southeast Asia and threatening the health of hundreds of thousands of people.

More than 2.6 million hectares (10,000 sq miles) had burned by the time the fires subsided in October. The fires were responsible for the same amount of greenhouse gas emissions as produced by the whole of Germany that year. The loss of tropical forests – the home of endangered species such as orangutans – was a hard blow for biodiversity. But it was the peat below the forests' surface that had the greatest impact on the climate.

Peat is a dense, soil-like material made up of partially decomposed organic matter which accumulates in swamp-like peatlands. Particularly in tropical regions, it can grow into a massive carbon store many metres deep. Worldwide, peatlands store more than 550 gigatonnes (billions of tonnes) of carbon globally. That's equal to 42% of the carbon stored in soil on the planet, despite peatlands covering less than 5% of the Earth’s surface area. Indonesia is home to some of the largest and most carbon-dense peatlands in the world.

Much of Indonesia's vast tropical forest – the third largest in the world – grows on peatlands. These soils are naturally wet, which keeps the peat from decomposing, but when forests are converted into palm oil plantations the peat dries out, leading them to rapidly degrade and release their carbon into the atmosphere. Globally, almost all oil palm is grown on lands that were once tropical moist forests.

The scale of Indonesian forest fires is a reminder to the world that addressing climate change means more than just shifting away from fossil fuels or adopting clean energy. Land also matters. Emissions from land-use, including agriculture, deforestation and peatland degradation, account for about a quarter of all global emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

(Source: Our World in Data/UN FAO, Credit: Adam Proctor/BBC)

Indonesia is ground zero for land-use change emissions. They typically make up around half of the country's total emissions, depending on the scale of fires in a certain year. The fires in 2015 made Indonesia the fourth largest greenhouse gas emitter globally, after China, the US and India.

Unlike temperate forests, fires are very rare in the tropics under natural conditions, because ample rainfall keeps the water table high. The problem is that oil palm, a non-native plant originally from West Africa, prefers dry land. As plantations expanded across Riau, North Sumatra and Central Kalimantan from the 1990s, canals were built to drain the land, putting peatlands at risk.

"Palm oil, much more than other crops, tends to expand onto tropical forests and peatlands with high carbon stock," says Stephanie Searle, fuels program director at the International Council on Clean Transportation. "Those impacts are really, really huge for the global climate."

Since 1990, palm oil has grown from a niche commodity to become one of Indonesia's main exports. The industry now encompasses 6.8 million hectares (26,300 square miles) of land, an area approaching the size of the Republic of Ireland. It produces 43 million metric tonnes of oil, 58% of the world's total, which is both consumed domestically and exported to regions including Europe, the United States, India and China.

"Palm oil has been a major driver of deforestation," says Annisa Rahmawati, a Jakarta-based forests campaigner at Mighty Earth, an environmental non-profit. "Insufficient law enforcement and disclosure created a situation that diminished our environment and harmed our people."

In 2021, six years after the historic fires, it seemed like progress was finally being made. While fires still burn yearly, including significant fires in 2018 and 2019, they were far less widespread than those in 2015. Furthermore, deforestation in 2020 had fallen 70% from its 2016 peak, according to Global Forest Watch data. The government's Peatland Restoration Agency and non-profits like Wetlands International and the Borneo Nature Foundation have re-wetted and restored hundreds of thousands of hectares of peatlands. In 2018, Indonesia implemented a ban on new oil palm plantations.

Meanwhile, entities like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), set up in 2004 after a wave of negative attention on the links of palm oil with deforestation, claim to have pushed supply chains to become more responsible. Major palm oil buyers such as L'Oreal, PepsiCo and Unilever have made zero-deforestation commitments.

But these fixes are not yet permanent. There has not yet been enough progress in transparency and responsibility in the palm oil industry to cut its links with deforestation, Rahmawati says. The RSPO has been criticised for enabling industry greenwashing, with a 2015 report from the Environmental Investigation Agency alleging fraud and a lack of credibility in its assurance processes in the organisation's supply chain certification scheme, and a 2019 follow-up finding many of these issues still remained. The RSPO responded that it is "committed to continuous improvement", and that the reports were inaccurate and did not take into account improvements to its assurance processes.

Indonesia's ban on new palm oil concessions expired in September 2021, and has not been replaced. The passage of a major new law in Oct 2020, meant to create jobs and spur economic recovery from Covid-19, paired with near-record high prices for palm oil globally, have led many to fear that a return to fires, peatland and widespread deforestation could again be on the horizon.

The fires in 2015 were, in many ways, a worst-case scenario. That year saw an extremely strong El Niño effect, which brought dry conditions to much of Indonesia. Once the fires reached the peat underground, they became extremely difficult to put out, and burned for weeks until rains finally came.

The massive scale of these fires acted as a wake-up call to Indonesia. Ahead of United Nations global climate conference in 2015 (COP21), Indonesia announced in its UN climate pledge to reduce emissions from forestry by 66% to 90% by 2030, depending on international assistance. To support this, in January 2016 President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo created the Peatland Restoration Agency (BRG) and tasked it with meeting new goals to restore 1.7 million hectares (6,600 sq miles) of peatlands within concession areas (including palm oil plantations), and 900,000 hectares (3,500 sq miles) of peatlands outside of these areas by 2020. The country's 2018 palm oil concession ban took this a step further, and in 2019 its moratorium on deforestation became permanent.

The BRG and other entities tasked with supporting peatland restoration faced a huge challenge. Peatlands are incredibly fragile, so they needed to work fast to restore those that were already being lost in order to limit CO2 emissions.

"If we are too late in restoring our peatlands, it will not be possible," says Nyoman Suryadiputra, a senior advisor at Wetlands International Indonesia. "Once the organic matter disappears, the ecosystem will change and it's no longer possible to rehabilitate it."

If anyone knows about this, it's Wetlands International Indonesia. The organisation has been working on peatland restoration across the archipelago since the late 1990s in the same provinces where the rapid expansion of oil palm plantations has transformed landscapes. Its latest project, begun in 2019, is working with 350 households in the province of North Sumatra to restore degraded smallholder palm oil plots around their villages.

In order to ensure that restoration is both effective and sustainable in the long-term, they take a community-centered approach. "We have to look after the community's livelihood," says Nyoman. "We cannot force them to restore their peatlands if they are hungry." That means providing alternative income streams to palm oil, such as other kinds of forest products or aquaculture. It also means ensuring locals are well-informed about the restoration effort and directly involved in monitoring it.

Many communities in Indonesia use peatlands for farming not only palm oil but other crops such as rice, maize and root vegetables, which they depend on for income, says Herry Purnomo, a researcher in peatland restoration at the Center for International Forestry Research in Bogor, Indonesia. "The development of community-based business models hand-in-hand with peatland restoration is a must," he says.

The BRG nearly met one of its goals, restoring 835,288 hectares (3,200 sq miles) of peatlands on state or community-controlled lands. But it failed, by far, to meet its other goal for peatland restoration within concession areas, restoring only 390,000 (1,500 sq miles) out of a planned 1.7 million hectares (6,600 sq miles) as of early 2020. The reason for this was BRG lacked the legal authority to force concession holders to restore peatlands, says Purnomo. "Peatland restoration outside concession areas is mainly the responsibility of the government, while inside the concession it is the concession holder's responsibility," he says.

Earlier this year, the organisation saw its mandate both extended and expanded. Now called the Peatland and Mangrove Restoration Agency (BRGM), it is tasked with restoring 600,000 (2,300 sq miles) hectares of degraded mangroves as well as a further 1.2 million hectares (4,500 sq miles) of peatlands by the end of 2024.

"I hope they can meet the updated goals," said Fadhli Zakiy, who leads the Peatland Restoration Information Monitoring System at WRI Indonesia. "We believe that they can, as long as the government supports them with an adequate budget and with regulations."

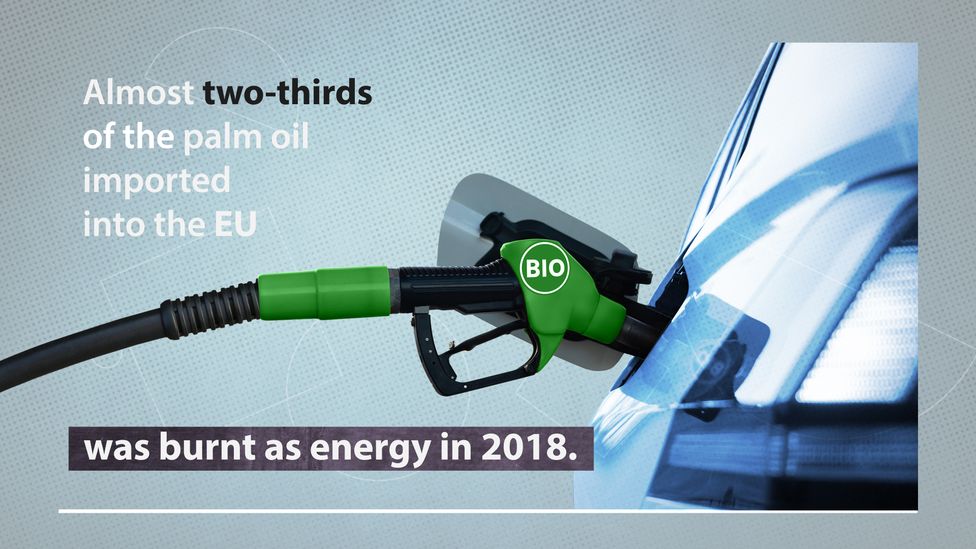

Palm oil is best known for its use in household products, but much of it is used to fuel vehicles (Source: Transport and Environment, Credit: Adam Proctor/BBC)

It is proper regulations, however, that have in the past several months become a key concern. The 2020 legislation on job creation raised alarm due to its streamlining of environmental regulations and changes which make land acquisition by corporations easier. Alongside the expiration of the moratorium on new palm oil concessions, it led to concern that the industry would expand onto forest and peatland. The government did not respond to a request for comment.

Juliana Nnoko-Mewanu, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch who has researched expansions of palm oil plantations in West Kalimantan, has expressed concerns that the job creation law could make things worse by "curtailing communities' and environmental experts' involvement in environmental impact assessments [and] accelerating licensing processes for [oil palm] businesses".

Combined, the new bill and the end of the palm oil moratorium "may end up increasing deforestation", says Arkian Suryadarma, senior forest campaigner at Greenpeace Indonesia. He says that Indonesia's peatland and deforestation policies are "not ambitious enough" to meet the 2030 goal.

Continuing peatland restoration will also require addressing the elephant in the room: peatlands which sit in existing palm oil plantations. Efforts to do land-swaps – from peat or high-carbon land to degraded land – haven't yet proven to have much impact, and canal-blocking and re-wetting on concession land has lagged behind activities on state-controlled land.

This impacts everyone, says Nyoman, because the peatlands are both interconnected and porous. "If a community is doing a rehabilitation project, but the private sector around it doesn't, then it will affect the peatland in the community land," he says.

While the government attributes the fall in deforestation between 2016 and 2020 to its own efforts, others believe it was due to unfavourable market forces. The last five to six years have seen a weak price for crude palm oil so there was not so much appetite for industry expansion, says Andika Putraditama, forests and commodities senior manager at WRI Indonesia. This year, though, the price of palm oil has hit a five-year record high due to shortages in the global vegetable oil market. "We need to be cautious to see if there is a spike in deforestation," says Putraditama.

The end result is a push-and-pull between all these forces. "A lot needs to happen for Indonesia to meet its 2030 [forestry and land-use] target," says Brurce Muhammad Mecca, an analyst at Climate Policy Initiative's Indonesia office. "Indonesia needs to provide a mix of policies that incentivise forest conservation and outweigh the economic incentives for deforestation."

Wherever the balance falls will have broad repercussions for the global climate. It will take a momentous effort – from civil society, the government and the global community – to protect Indonesia's critically important tropical forests and peatlands.

--

Data research and visualisation by Kajsa Rosenblad

Animation by Adam Proctor

--

Towards Net Zero

Since signing the Paris Agreement, how are countries performing on their climate pledges? Towards Net Zero analyses nine countries on their progress, major climate challenges and their lessons for the rest of the world in cutting emissions.

--

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

The everyday ingredient that harms the climate - BBC News

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment