Houston seems to have the ingredients for a major biotechnology hub, starting with a medical district boasting four medical schools, world-class hospitals, and leading research centers, and developers planning lofty projects to create life sciences districts to rival Boston, Silicon Valley and San Diego.

It’s a wildly ambitious vision, but given time, Houston could get there, said William “Bill” McKeon, CEO of the Texas Medical Center.

“It doesn’t happen overnight. It took Boston 15 or 20 years to build up their life science presence,” McKeon said. “It starts with a couple of companies in a great collection of academic centers.”

Houston is far from the first city with leading medical and research institutions to dream of biotech riches, but history shows that it takes more than just brilliant minds and a build-it-and-they-will-come strategy. Metropolitan areas from Atlanta, home of the Centers for Disease Control, to Rochester, Minn., home of the Mayo Clinic, have also sought to develop biotech clusters, with limited success.

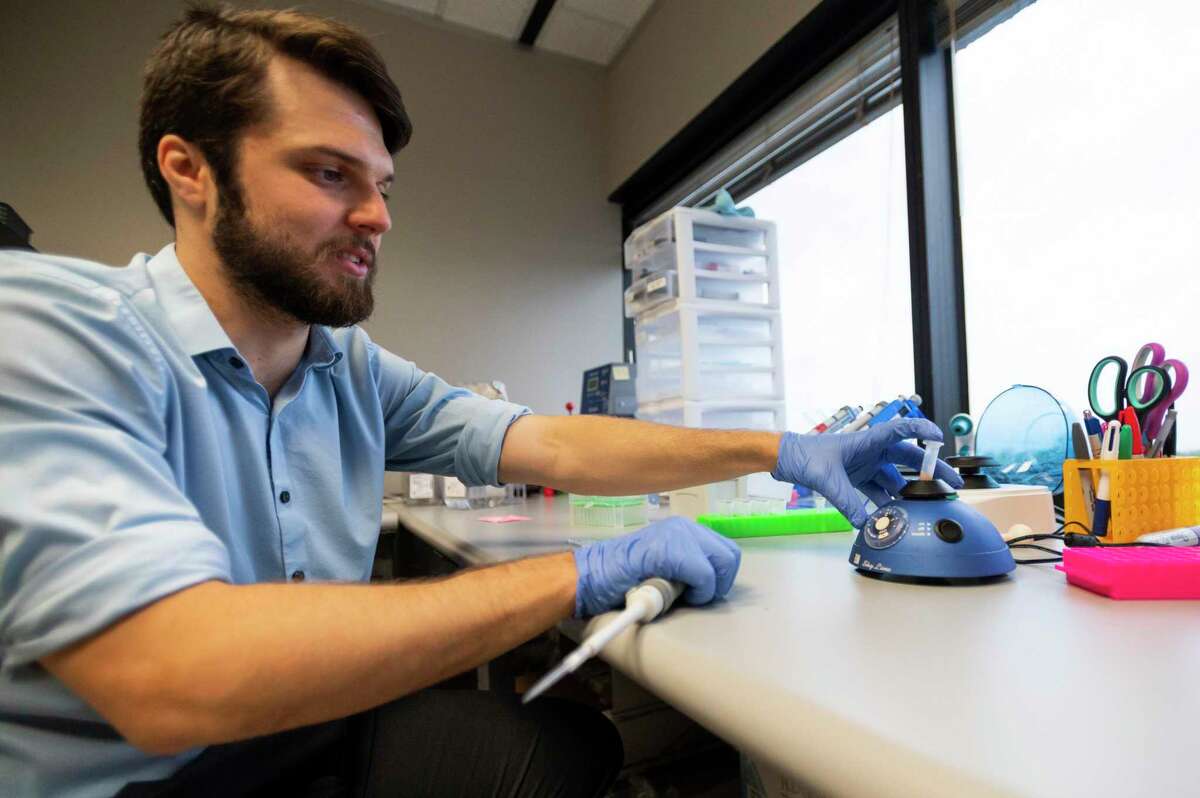

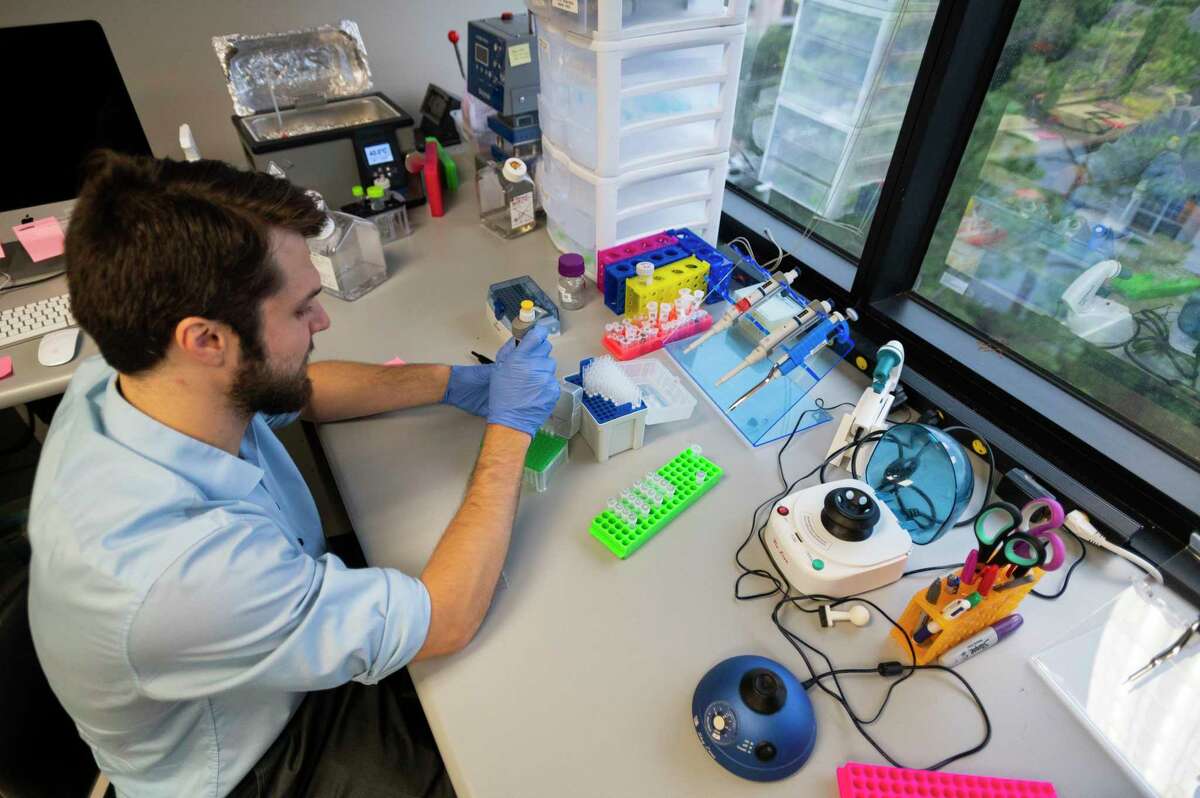

Jacob Quick prepares a sample for the Brevitest sample processing unit in the R&D lab in Fannin Innovation Studios Tuesday, May 24, 2022, in Houston, Texas.

Justin Rex, Houston Chronicle / ContributorLike Houston, experts said, these regions lack the critical mass of venture capital and entrepreneurial expertise to move scientific discoveries from the laboratory to the market. Biotechnology companies are extremely risky investments, burning to through tens of millions and hundreds of millions of dollars over a decade or more to develop new drugs — all with the chance that a poor clinical trial will spell the end of the prospective drug and the company.

Venture capital firms willing to make such bets are hard to find in Houston. The region attracted $731 million in venture capital for biotech companies compared to $12 billion in the San Francisco Bay area and $14 billion in Greater Boston, according to Crunchbase, an online platform that tracks private and public companies.

The concentration of venture capital on the coasts makes it all the more harder for other regions to build significant biotechnology clusters, said Joseph Cortright, an economist who has studied biotech development. Venture capitalists want to attend meetings, visit companies and stay in the loop about the latest developments, so they prefer to invest in companies near their offices, Cortright said.

“A venture capital firm is not just writing a check and hoping for good things to happen,” Cortright said. “They take seats on the board, and they help guide the firms through that process. It’s a very kind of hands-on, time-intensive activity.”

‘Locked in’

The biotech industry took root on the coasts in the 1980s. Some of the oldest, most prestigious academic institutions are located there, as well as some of the largest pharmaceutical companies. The pharmaceutical giants Merck and Pfizer were born in the New York corridor in the 19th Century.

As scientists gained a better understanding of DNA and genetics in the ‘80s, the emerging biotech industry moved to places beyond where the pharmaceutical companies had a stronghold. Clusters began to form in places like Boston and San Francisco, where venture capital firms were well established largely because of the thriving tech scenes in these areas.

“Once the clusters formed in those locations,” Cortright said, “that more or less locked in where they are.”

Houston, while far behind the established biotech centers, has nonetheless built some momentum toward expanding its biotechnology and life sciences sector. There are about 1,700 life sciences companies, hospitals, health facilities and research institutions employing than 320,000 people in health care, biotech and related fields in the area, according to the Greater Houston Partnership.

Venture capital investments in Houston biotechs have increased sevenfold to $731 million in 2021 from $83 million in 2017, according to Crunchbase. The Houston developer Hines and the Levit family plan to redevelop more than 52 acres near the Texas Medical Center and create Levit Green, a life sciences district of offices, laboratories and research facilities.

Jacob Quick prepares a sample for the Brevitest sample processing unit in the R&D lab in Fannin Innovation Studios Tuesday, May 24, 2022, in Houston, Texas.

Justin Rex, Houston Chronicle / ContributorAnother project launched by the Texas Medical Center, called TMC3, is developing a 37-acre biomedical research campus. Construction for the first phase of the project is backed by $1.8 billion in financing from life science investment and property development teams.

The state is also providing support through the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas. Created in 2007 with $3 billion in funding primarily to support academic research, the Legislature in 2019 authorized another $3 billion for the program. About 17 percent of the money helps biotech companies develop cancer treatments.

In March, the Texas Medical Center said it doubled the size of its venture capital arm, TMC Venture Fund, to $50 million. The fund, however, invests across the country and many of its portfolio companies are outside of Texas.

Discovered in Houston, headquartered elsewhere

Finding local investors was a problem for Dr. Raghu Kalluri as he tried to launch a company to commercialize his research into treatments for pancreatic cancer — one of the most aggressive and deadly types of cancer.

Kalluri, a researcher at MDAnderson, was developing a technology that uses exosomes, particles that cells release, to fight cancer cells. Exosomes carry genetic information and proteins to other cells, and Kalluri and his colleagues had an idea to use the exosomes to also carry drugs targeting cancerous cells.

His idea of using exosomes was too novel for local investors, who were unfamiliar and uneasy with business propositions that required so much capital upfront and so many years before they might pay off, he said.

“The general thinking here is that it needs to be something that's going to go to patients right away or it needs to be (in the early stages of clinical trials),” Kalluri said. “It needs to be somewhat low risk.”

Amanda Gibbens works in the medical device lab in Fannin Innovation Studios Tuesday, May 24, 2022, in Houston, Texas.

Justin Rex, Houston Chronicle / ContributorHe soon found that investors in other parts of the country were more receptive to newer science. In 2015 and 2016, the company received tens of millions of dollars of investments from Arch Venture Partners, a Chicago venture capital firm, and the venture capital arm of the Boston financial services company Fidelity Investments.

Kalluri and others launched the company, called Codiak Biosciences, in Cambridge, Mass., in 2015. By the start of 2016, the company had raised $92 million.

Kalluri now serves as a scientific adviser to the company. Codiak, which has products in human clinical trials, employs 102 people, according to SEC filings, and has raised about $235 million in four funding rounds. It launched a successful initial public offering in October 2020.

Codiak is not the only example of innovation from Houston getting commercialized elsewhere. The issue isn’t always funding. Sometimes it’s talent.

Shallow pool for senior leadership

UTHealth has an office of technology that handles the commercialization of discoveries coming out of the six schools in the University of Texas system. It licenses the patents to companies, which would pay the university royalties if drugs get to the market.

About 60 companies license UTHealth technology — about a third are from out of state. It’s not uncommon to see the university to work with companies on either coasts, said Dr. Bruce Butler, vice president of research and technology at University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Another big advantage for established biotech centers is their deep pools of executives experienced in leading companies through drug discovery, clinical trials, regulatory processes, and sometimes acquisitions by major biopharmaceutical companies.

“On the West and East coast, there are more experienced CEOs available because there are so many companies,” Butler said. “If you look at any successful biotech company, the people in the C-suite all have multiple companies under their belt.”

Paras Gupta, left and Amanda Gibbens insert a catheter into a model bladder in Fannin Innovation Studios Tuesday, May 24, 2022, in Houston, Texas.

Justin Rex, Houston Chronicle / Contributor

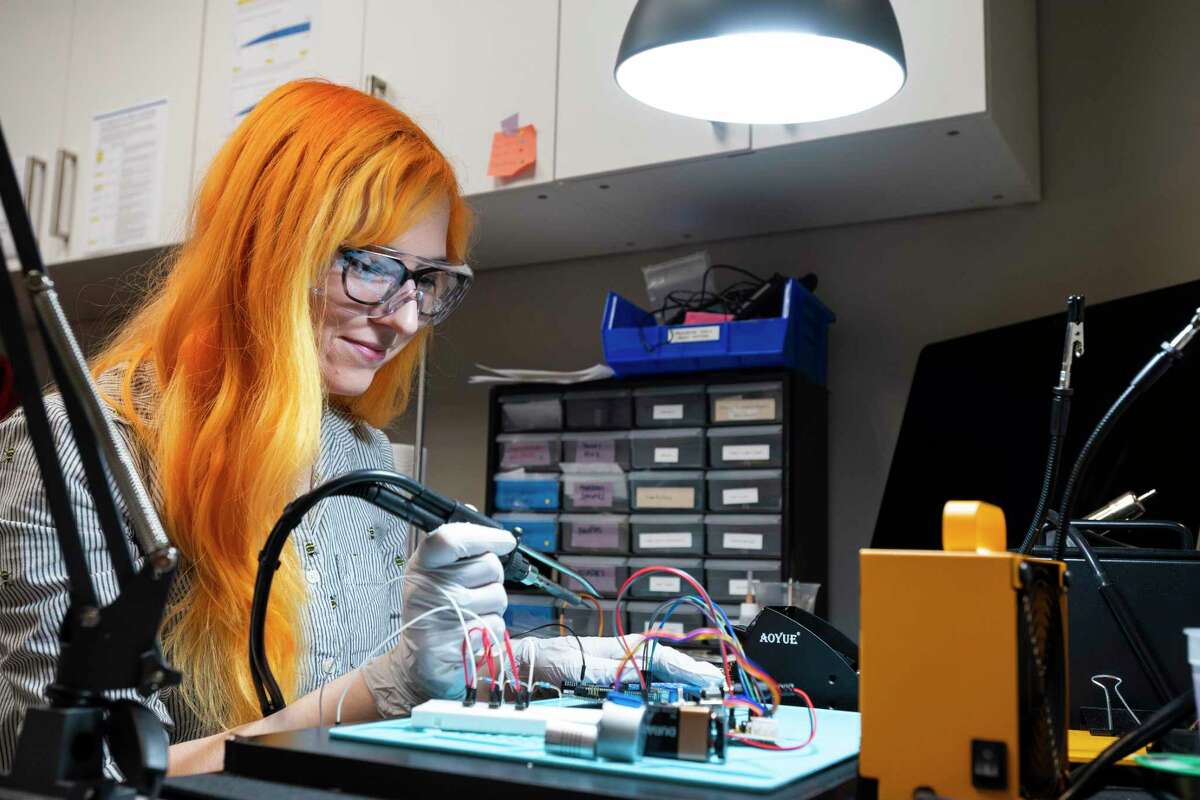

Amanda Gibbens solders an electric motor for a urology device in the medical device lab in Fannin Innovation Studios Tuesday, May 24, 2022, in Houston, Texas.

Justin Rex, Houston Chronicle / ContributorParas Gupta, left and Amanda Gibbens insert a catheter into a model bladder in Fannin Innovation Studios Tuesday, May 24, 2022, in Houston, Texas.

Fannin Innovation Studios, a life sciences incubator in River Oaks, is trying to build such a talent pool.

The skills needed make scientific discoveries and build a business are completely different, said Dr. Atul Varadhachary, managing partner at Fannin Innovation Studios. So, the incubator runs apprenticeship programs to teach researchers about commercializing scientific discoveries, covering areas such as grant writing, market analysis and business development.

So far, Fannin Innovation Studios has spun out four companies, all of which are still located in Houston. One of the companies is developing a drug that helps protect against respiratory diseases such as SARS and MERS, and another created a COVID antibodies test.

“For some reason,” Varadhachary said, “we seem to think you can take a great academic researcher and they’ll be able to do drug development without experience.”

Making it work in Houston

Pete O'Heeron is the CEO of FibroBiologics, Houston biotech developing an alternative to stem cell therapy. The technology uses fibroblast, the most populous cell in the body, and O’Heeron believes it could be more effective than stem cells in treating diseases such as multiple sclerosis, cancer and degenerative disc disease.

O’Heeron said he doesn’t intend to move his company because Texas Medical Center offers facilities and a large sample of patients for clinical trials. For now, he relies mostly on angel investors to fund his company.

But if more companies like his are going to stay in Houston, investors need to be willing to take chance on them, he added.

“In Houston, we just need a group of people or a coalition of people that are investing in these companies at an early stage,” O'Heeron said, “and betting on these entrepreneurs and their technologies.”

More Houston and Texas stories

Houston could be a biotech hub. Here's the one ingredient that the city is missing. - Houston Chronicle

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment